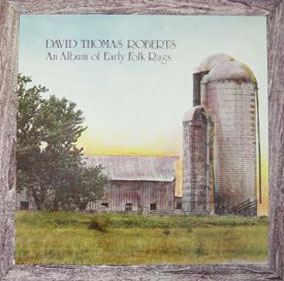

An Album of Early Folk Rags

(Stomp Off Records, York, PA, 1982 - LP)

Status: Out of Print

Introduction

Of all the piano rag types now recognized, the folk or country rag lends itself the least readily to definition. Unlike classic ragtime, which was dominated by a prolific composer (Joplin) and a single-minded publisher (Stark) whose standards largely defined the genre, folk ragtime developed under no such guidance. Much of it seems to have been composed by people working in isolation or in contact with a few local ragtimers. While many of these rags were issued by major companies, others were preserved thanks only to small-town publishers; and while some of the latter sold well, it is apparent that a number of these were issued at their composers' expense with little hope of financial reward. Thus a figure like C. L. Woolsey may have had no qualms about publishing a rag as idiosyncratic as Mashed Potatoes or one as physically demanding as Medic Rag. It seems to be the variability of such material that has encouraged so much confusion over the term "folk ragtime," causing at least one observer to question its usefulness. May the following guideline remedy this to some degree and serve those who seek to formulate their own definitions:

Folk Rag: A ragtime composition of predominantly rural musical origin, frequently containing features that deviate from the European rules generally adhered to in classic ragtime.

But one question presents itself and, I expect will persist regardless of efforts to answer it: how can "rural musical origin" be precisely determined? It probably can't. In the case of early folk rags, we are too removed from the origins to sort out the components with absolute confidence, and in dealing with contemporary folk rags, the best of which reflect more recent folk/popular sources, one might question whether much material should be characterized as rurally derived or merely influenced by material bearing some nebulous rural connotation. And could the latter warrant the publication of the term "folk rag"? It is doubtful that most meticulous motivic, rhythmic and harmonic breakdown would yield certainty of the folk type's identity for everyone, let alone a definition with which all would agree.

Folk ragtime has always been less trendy than other ragtimes. A high percentage of the folk rags published after 1905 and even during the teens scarcely reflect the development of popular music after the advent of published ragtime. This is not to suggest that the folk rag is a closed form – it provided and continues to provide some of ragtime's most inventive and flexible outlets – but rather that it flourished in the framework of its own tradition, which was not so susceptible to the assimilation of changing characteristics of the mainstream. This independence is inherent in the folk rag's nature.

The most obvious element of the folk rag's homespun distinctiveness is its predilection for the unconventional. "Improper" part writing procedures, parallel octaves and fifths, unpredictable key changes and strains comprised of odd-numbered totals of measures (instead of the usual 8, 16 or 32) are frequent in folk rags. Whereas classic ragtime evinces respect for the basic rules of part writing (even in the case of James Scott, who occasionally strayed), there is often no such concern in the works of folk composers. Undoubtedly, unawareness of these rules was responsible for many instances of unusual writing. But this removal from classical expectations is not necessarily a handicap, as the open-minded listener discovers; some of the most beautifully conceived writing in ragtime is found is such "ingenuous" pieces, compositions which someone working under the control of European-derived taste would not likely have written.

Folk rags are capable of dispelling as forcefully as classic rags the provincial notion that ragtime's mood palette is limited. The best of these pieces are intense and demanding listening experiences, forcefully engaging in their expressions of pensivity, wistfulness, carefreeness, irony, jubilation and anguish. They comprise a body of music no "lighter" than the Chopin Mazurkas.

All of the rags presented here are obscure and underplayed by the standards of familiarity now accorded classic ragtime. While some of them are internationally available in reprint, Teddy in the Jungle, Texas Rag and Mizzoura Mag's Chromatic Rag are about as unknown as works can be without being lost. But folk rags are now performed with greater frequency and by more performers than since the early ragtime days. The prospect of composing in the folk vein is becoming increasingly attractive to young ragtime writers, as evidenced by the music of eighteen year-old John Hancock of St. Louis. At last the quintessential art form of down-home America is being recognized and loved.

Special acknowledgement is due Trebor Jay Tichenor, without whose uniquely distinguished research many folk rags and much information concerning them would be unknown, if not lost.

Track Listing

- Teddy In The Jungle (by Edward J. Freeberg, 1910; Rinker Music Co., Lafayette, Indiana). Freeberg was a piano tuner and bandleader who published two countrified rags in his home town, The Purdue Spirit (1909) was a humble prelude to one of the most alluring of all folk rags, Teddy in the Jungle (the cover depicts Roosevelt stalking wild game) is a prototype of pure Midwestern folk ragtime with its affectionate lyricism and casual structure. The second strain, a particularly moving sample of folk lyricism, is conveniently notated as a 32-bar strain to be played twice, although it has the effect of a 16-bar structure played four times.

- Pride Of The Smoky Row (Q Rag) (by J. M. Wilcockson, 1911; J. M. Wilcockson Music Co, Hammond, Indiana). There is a story that the shadowy J. M. Wilcockson spent time in New Orleans and as a result gave his great rag the name used there to denote the line of cheapest cribs in Storyville. The personification of ragtime poignancy, Pride of the Smoky Row is at once fancy and pathetic; its pseudo-gaiety amounts to a glittering tragedy. Hearing it is reminiscent of finding a valentine of an ancestor who died young.

- Mizzoura Mag's Chromatic Rag (by H. H. Farris). An oddity that has survived only as a piano roll, this piece sports a B section consisting of 14-2/3 bars; that is, 14 bars are in 2/4 and one is 3/8. The effect is so jarring that some listeners assume that the roll is simply flawed, a possibility not to be disregarded.

- Mashed Potatoes (by Calvin Lee Woolsey, 1911; C. L. Woolsey, Braymer, Missouri). Dr. Lee Woolsey (1884-1946), who spent most of his life in the town of Braymer in northwest Missouri, is still remembered by many residents of Caldwell and Ray counties as a ragtimer as well as the family doctor. A man of varied interests who required little sleep, his free time was devoted to music, building cars and radios, cooking, and making dolls for the babies he delivered. He died of a heart attack in his garage. Mashed Potatoes is his best remembered effort in northwest Missouri and is still played there by a few people who heard him perform it. Woolsey played his rags at slow and moderate tempi. The late Mike Toomay, who learned all the Woolsey publications and knew the doctor well, took Mashed Potatoes very slowly and in a slightly swinging fashion, creating a snappily accented sashaying effect. On my first trip to Braymer, Mike Toomay gave me Woolsey's piano, which had been stored in a shed on the Toomay farm for years.

- Kalamity Kid (by Ferdinand Alexander Guttenberger, 1909; Ford Guttenberger, Macon, Georgia). J. Russel·Robinson, who knew Guttenberger in Macon is credited with the arrangement of this piece. The A section consists entirely of a circle of fifths, while B and C feature circles of fifths in the cadences. The 12-bar interlude, culminating in an ascending scale of chromatic octaves, is a surprising feature.

- X. L. Rag (by Lee Edgar Settle 1903; A. W. Perry & Sons Music Co., Sedalia, Missouri). Edgar ''Jelly'' Settle is believed by many people from his hometown of New Franklin, Missouri, to be the author of The Missouri Waltz. There are accounts that he played it regularly in central Missouri before it was issued by Frederic Logan (who obtained the tune from John Valentine Eppel who is supposed to have stolen it from Settle); in that area it was known as Graveyard Waltz. Settle was a big, bald man with powerful hands who began touring in vaudeville at 17. What can be said of his only known rag, that gorgeous haystack-of-a-piece published in Sedalia and dedicated to a country brothel? Let this suffice: it is the ultimate hymn of outstate Missouri.

- Texas Rag (by Callis Wellborn Jackson, 1905; C.W. Jackson, Dallas, Texas). Callis Wellborn Jackson remains as recondite a figure as there is in published ragtime, but his Texas Rag is the darling of folk rag lovers. With its lovely parallel octaves in the B strain (in which the bass doubles the melody), bi-tonal reference in the D (D flat major and D flat minor simultaneously) and proud, hymn-like C, which returns to conclude the piece, Texas Rag is the most rewarding of all early folk rags.

- Cole Smoak (by Clarence H. St John, 1906; John Stark & Sons, St. Louis, Missouri). The best of three surviving St. John rags, this one ranks among the best in Stark's catalogue. Start referred to St. John as "the present-day king of ragtime invention." Not surprisingly, Cole Smoak has more in common with classic rags than the other pieces on the LP -- which renders the blue note in the innocent B strain that much more memorable. The last section is, in effect, a chorale; it a model of climactic power in the culmination of an AA BB A CC DD rag.

- Sweet Pickles (by Theron C. Bennett, first published under the pseudonym "George E. Florence", 1907; Victor Kremer Co., Chicago, Illinois). Theron Bennett (1879-1937) was from Pierce City, Missouri, an Ozark town near the state's southwestern corner. It is now generally agreed that he was the "Barney & Seymore" to whom The St. Louis Tickle was credited. His immense scrapbook is housed in the library at Pierce City. Of the many folk rags published in Chicago, Sweet Pickles is one of the most original and well-made.

- Back To Life (by Charles Hunter, 1905; Charles K. Harris, New York City, New York). What little is known of the tragic life of the Tennesseean who was early folk ragtime's most gifted exponent is best told in Rags and Ragtime (Jasen & Tichenor, the Seabury Press, 1978). This is his last and strangest publication, consisting of four loosely assembled sections. The most notable feature is the G minor to F major progression in the first strain, reminding one of breakdowns performed by bluegrass bands.

- Queen Of Love - Two Step (by Charles Hunter, 1901; Henry A. French, Nashville, Tennessee). This is the definitive country march. Quaint, stately and unabashedly melancholy, it is a fitting introduction to Hunter's rural lyricism.

- Holy Moses (by Cy Seymour, 1906; Arnett-Delonais Co., Chicago, Illinois). No biographical information concerning Cy Seymour is available. The high point of Holy Moses is the fervent C section, recalling old hymns and the roots of country music.

- Sponge (by Walter C. Simon, 1911; Gruenewald Music Co., New Orleans, Louisiana). Walter Simon is listed in some of the New Orleans directories of the century's first decade as a music teacher, but he was working as a salesman for the Gruenewald Company when Sponge was published. He apparently left New Orleans in the teens. Could he have been the Walter Simon born in Cleveland in 1884 who was an organist, inventor and author of salon pieces? Sponge (the title is a synonym for "pimp") abounds with gaudy eccentricities. Wildly deviant part writing, raw fourths and fifths, and the absence of the second strain's 16th bar on its second and third statements (the latter instance ending the piece) are immediately arresting characteristics. The introduction, A section and variation of A (all in F minor) are as sinister as the rag's title, while the brief C sounds like a sarcastic meditation upon Old Folks at home. But it is the B, with its garish, clanging treble octaves stuffed with fifths and its bass of fourths and fifths that sums up Sponge's ironic personality. When I gave its first recording in 1978, I called it "one of the most compelling adventures in ragtime." I reaffirm that description of this elegantly mysterious and disturbing piece.

David Thomas Roberts, January 13, 1982