(Stomp Off Records, York, PA, 1984 - LP)

Status: Out of Print

Introduction

I have little interest in supplying listeners with "purely musical" analyses of my works. Such observations can be made by others, as the "purely musical" is generally evident, or at least potentially evident, to musically educated listener-students. I find it irritating that so many serious composers who write their own liner/program notes devote the space to formal discussions that could have been authored by the common academic. Not only do I feel obligated to here leave alone formal analysis, I believe that to devote more of this space than is essential to the merely objective would be wasteful. I am interested in sharing with you information about this music that could have reached you from no other source.

Since early childhood I have been writing, painting and composing. I remember no early time when my identity was ambiguous, my goals uncertain or my inclinations unrevealed. I did not identify with people around me but with "historical" figures. The assumption that I was akin to the people whose acts were preserved in books and that I too would enter the encyclopedias seems to have always been with me. I felt estranged from children and adults, particularly the former, and remained disappointed in both. The anguish of school life was a force that persists in affecting my associations with all people.

Moss Point is a paper milling town on the Escatawpa River just off the Gulf coastline. There the coastal marshworld meets river swamp to compile a roaring dictionary of greens. Bordering the wetter passages are pockets of the vast pine forests which overspread south Mississippi. To the north, along the Pascagoula River, there is preserved one of the few major river swamps remaining intact in North-America. Southeast of Moss Point, on the fringes of the swampy terrain that melts into bayous and open water, is the village of Kreole, and to the southwest is the old port and ship-building center of Pascagoula. In this collage of vegetation, industry and beach I was born.

One of my most reassuring associations with Moss Point and Kreole is the memory of the late night beeping and clacking of the paper mill as I lay on the verge of sleep. Moss Point... that sad river town with its box cars, shrimp boats, dark greens, half-cleared lots and starvation for intimacy whose somber lyricism goes on quivering in my dreams, on desks, in pianos and windows...

I have always been moved by props, often far more than by the human activities for which they were devised. An assembly of objects without the visibility of their makers or utilizers intimates qualities that will always preoccupy me. The untranslatable body of intrigues voiced by isolated houses, shut-down communities, lost articles, farm or construction equipment unattended, warehouses, railroads, the props of the highway... Such quiet marvels are central to my visual life. And not only are they carriers of the most urgent mysteries, evocations and possibilities; they are vehicles of the deepest, dire longing.

I have sporadically pretended to love objects more than people. There have been many favorites-road signs, gravestones, airships, devices of punishment (1 owned a full-sized, functional guillotine and stocks which I displayed in the yard when I was eleven), wind stockings, and, of course, random combinations. Utilitarian artifacts even more than art objects received attention that, under other circumstances, could have been claimed by humans. Objects in combination with terrain and flora came to uniquely illuminate the identity and need of love, its anticipation and idealization. Through the land-object collaboration I possessed a conduit of love. Through fields, subdivision streets, houses at swamp-side, ballparks and pine stands, my love of women screamed and nourished its irrepressible life.

Much of my ragtime is associated with eroticism. Even in those rags which are not actively informed by erotic memories or imaginings, an eroticized mode is usually in effect. I have always viewed this sexualized cognizance-whether lending itself to characterizations of "innocence" or "experience" -as an essential dimension in ragtime expression. In The Early Life of Larry Hoffer a recognition of the anti-sexual is taken into account; the subversion of the erotic on various levels, the sense of being sexually passed by and denied all semblance of erotic affection, and ultimately a pervasive rage toward sexuality are phenomena marking the biography of Hoffer and my private image of him. One of my most mellifluent rags, Leslie Bovee (1980) is named after a pornographic film star and seeks to register the haunting and tangled plethora of properties experienced in the source. Elsewhere in my ouvre are more celebratory erotic pieces. It is in Waterloo Girls as in perhaps no other composition of mine that the dynamism of desire-with its revelatory hope, anticipation and illumination of freedom, and, also its fears, piquant evocation of the innocence-experience duality and all the peculiar vestiges of repression and deprivation that in the end must serve desire's complication and intensification - is so unabashedly, triumphantly affirmed.

Eclecticism is a feature of all my work. Figures as diverse as Pierre Reverdy, Charles Ives, Paul Klee, Scott Joplin, Andre Bret6n, Hank Williams and Adolph Wölfli have deeply affected my production. Although my most evident need is to write, I can't envision a tenable life without painting and composing. Not only are my mediums mutually informing; they are elements of the same invention.

Why is the composing of ragtime a component in my string of necessities? Because I perceive too much inventiveness, musicality and sheer love in the medium for it to be otherwise. I have written before of the piano rag's attraction for the composer who is excited by the challenges of amalgamation, and particularly for the thinker who thrills to the combination of various "vernacular" and "art" musics. But these interests, which I certainly entertain, provide no basis for my need of ragtime. I need it because of its insistent intimacy, because it affected me in early childhood as did nothing else, because it possesses a very particular poignancy that finds no other outlet. The attitude of ragtime is uniquely Romantic; it embodies a Romanticism without affectation or inflation. It is miniaturized, concentrated, fomenting. Ragtime is a child's Romanticism.

Ragtime can never be aloof or uncaring. It must trust you. Great ragtime compositions communicate an urge to share deeply, to know and to be known. However anguished the expression of a rag it does not culminate in evasiveness or self-protection. No pain-infused rag ever had a prayer of mocking or witticizing its way to safety. Grief is ragtime's negative mode, not cynicism.

How could I not compose rags?

Track Listing

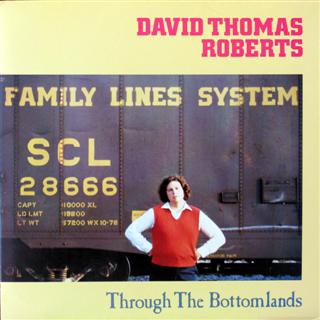

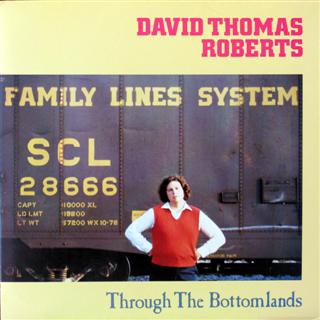

- The Family Lines System (1980). For a New Orleans concert in May, 1983, I wrote of this piece: "A driving composition influenced by country music (as well as the Latin material whose influence sings through my ragtime world), The Family Lines System is named for the railroad corporation that provides the South with its most familiar box cars, engines and cabooses." That June I learned from a Family Lines employee that the company had now become the Seaboard System. He gave me a brochure featuring the new insignia and an explanation of the new name. So it is that the railway equipment so symbolic of the crescent sweep from Louisiana to the Northeast will eventually disappear.

- Through The Bottomlands (1980, for Vicki Picou). Bottomlands are defined as low-lying areas near rivers which contain rich alluvial soil. But for me the connotation is far richer than the definition. The word "bottomlands" evokes wetlands as well as rich farmland; it recalls rural isolation, tiny, half-tilled farms bordering swamps, the poverty of families reliant upon sharecropping and meager vegetable outputs, dreams of the land and its human tenants existing inseparably...

- For Teresa (1974, for Teresa K. Jones). The year-and-a-half spent at the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg remains the most cherished period of my life. For Teresa is a preservation of the most wondrous of these days. Unlike my later rags, it is dominated by the spirit of pure classic ragtime, which I played daily at that time. It is one of fifteen pieces I recorded via piano roll in Turlock, California in October, 1979.

- The South Mississippi Glide (1978). This piece, which I consider to be as successful in its own way as Through the Bottomlands, may be viewed as a study in restrained intensity. Its first strain contains a quote from the hymn. "Just As I Am."

- Poplarville (1979). What is the town of Poplarville? A shadowed beehive of windows and crossroads clicking helplessly in the pinelands, the seat of endlessly macabre Pearl River County, Mississippi, a cornerstone of imaginary eroticism, a dream-fed complex of hermetic longing. In a domain where towns and country communities are strewn through the woods like lost maps, Poplarville is a spectral hub. To the south and west of it are stationed the centers of many memorable nocturnal adventures-Carriere, McNeil, Pine Grove Road, Crossroads and the terrifying Henleyville. In location and identity Poplarville is the incarnation of the town-and-land mystery so changelessly near the center of my consciousness.

I fear the composition Poplarville. Its floral fabric is too heavy with perverse inferences and grim potential to touch without a shiver. I must approach it as I might approach a complex being or a community. And if its essence is ultimately private, let it be a privacy inviting the most wide-eyed exploration.

- Lily Langry Comes To The Midwest (1979). Lily Langtry (born Emilie Charlotte Le Bretón, 1853-1929) was the erotic darling of late Victorian England and most of the Western world. She toured the States in the 80's and 90's and performed in Chicago and St. Louis. One newspaper editor in the city of Tom Turpin (being apparently as provincial then as it is now) was so galled at Lily's open maintenance of a lover in her hotel that he encouraged St. Louisans to boycott her performances.

- The Early Life Of Larry Hoffer (1977). The remarkable, alienated Mississippi composer, visionary and poet Larry Hoffer was born in Poplarville in 1951. He lived in Mars Hill and Sardis, Mississippi during his earliest years before being brought by his parents to Meridian where he has frequently lived since. Showing great aptitude in the first years of his life, he was discouraged by his mother from studying piano and composing. He did manage to find a modicum of training, however, and eventually arrived at the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg where I met him in 1973. His brilliance and relentless devotion to his earliest visions in the face of neglect, isolation and opposition comprise a heroism that should exhilarate every true outsider. We both lived in New Orleans through 1982, and it was from there that I last heard of him in the summer of 1983.

The Early Life of Larry Hoffer is not only reflective of his childhood; it is associated at least as closely with an adulthood little unlike the adolescence. It is concerned with the nearby world about which he only dreamed as well as with the dark and marvelous Mississippi interior from which he came; the urban frights of New Orleans, the strip joints, tourism and port city toughness of the Mississippi coast, the even more foreign Gulf centers of Mobile and Pensacola-these elements are counted in my link to Larry Hoffer and to all who peopled my own early life.

- Braymer (1979-1980). In the summer of 1979 I went searching for ragtime composer Calvin Lee Woolsey (1884-1946) around his native Braymer in northwest Missouri. The late Hugh Paul (one of the children on the cover of Woolsey's Mashed Potatoes) was my guide. Lonely and lyrical northwest Missouri fascinated me more than Woolsey with its contorted hills and unchanging farms. Braymer itself, an archaic little town planted in lostness, could not have been more satisfying or compelling. I revisited Braymer in September and interviewed Charlie Reno, a ninety-four year-old retired auctioneer who had known Woolsey since grade school. Near the end of 1979 Charlie was beaten to death on his property by a local farmer who suspected the old man of hording a fortune. By that time the long-ill Mike Toomay, who had given me Woolsey's piano on the first trip, had committed suicide. It was after hearing of this that I began Braymer.

- Rock Island (1979-1980). This piece, like Muscatine, was written after a trip from Chicago to eastern Iowa in early November, 1979. It was via Rock Island that I crossed the Mississippi River into homey and delectable Iowa. As clearly as in any of my folkier pieces, Rock Island sings with my consciousness of early small town ragtime.

- Tallahassee (1975). After having to leave Hattiesburg suddenly in March, 1975, I became interested in moving to Florida State University in Tallahassee at the urging of composer James Sutton. We look two trips there that year (and were accompanied by Larry Hoffer on the first of these) to prepare our relocation. Jim made his move in autumn; I didn't arrive until January, 1976.

Tallahassee was written after the second visit when I viewed Tallahassee as a haven from menace. I began the second section in the lobby of a Pensacola hotel while Jim saw his grandmother upstairs. The third strain is labeled "Trio-Chorale" in the score.

- Waterloo Girls (1980). Its title referring to a southern Illinois town through which I pass en route to St. Louis from Carbondale, this work is a memento of my travels through countryfied Mid-America. A handful of details have been changed since this recording was made. This variance is made particularly interesting by the appearance of Morton Gunnar Larsen's impassioned, dancing 1983 recording on the Hot Club label, which is in keeping with the piece's later form.

Although I have betrayed it in many works and lesser actions, I am committed to optimism. I offer Waterloo Girls as a testament to an optimism thriving on anguish and pointing, a little coquettishly, to rapture.

Dedication

This album is for Fred Dale, Steve Shepard, Reese Partridge, Andy Campbell, Larry Hoffer and the others who have so bravely devoured the poetry of the bottom lands with me.

I have always been frightened of the cover of Mandy's Broadway Stroll. It features a girl with a parasol, apparently a prostitute, staring at the viewer from the street: (The red light blocks of Broadway in Nashville were called "the stroll.") It is her pathetically sinister face, which registers a malevolence that flares independently of the rag's title, that so upsets me. The composition's nature is one of the most representative in the ragtime temperament; that Janusian spirit which brightly strides forth and grieves simultaneously, its body stamping proudly before onlookers as its face unabashedly contorts with tears. I view this spirit as the surest guide to ragtime's essence; it has been with us from Sunflower Slow Drag to The Alaskan Rag to John Hancock's Dixon.

I have always been frightened of the cover of Mandy's Broadway Stroll. It features a girl with a parasol, apparently a prostitute, staring at the viewer from the street: (The red light blocks of Broadway in Nashville were called "the stroll.") It is her pathetically sinister face, which registers a malevolence that flares independently of the rag's title, that so upsets me. The composition's nature is one of the most representative in the ragtime temperament; that Janusian spirit which brightly strides forth and grieves simultaneously, its body stamping proudly before onlookers as its face unabashedly contorts with tears. I view this spirit as the surest guide to ragtime's essence; it has been with us from Sunflower Slow Drag to The Alaskan Rag to John Hancock's Dixon.